Chapter 2. The Time-Quality Curve

Where you invest your love, you invest your life.

Awake my soul

Mumford and Sons

Doing things takes time.

Sometimes that’s annoying, but at least some of the time it’s the whole purpose. Either way, it’s hard to avoid the fact that we have to spend time to get anything done. Doing things well often takes more time again, and that can also be annoying or purposeful.

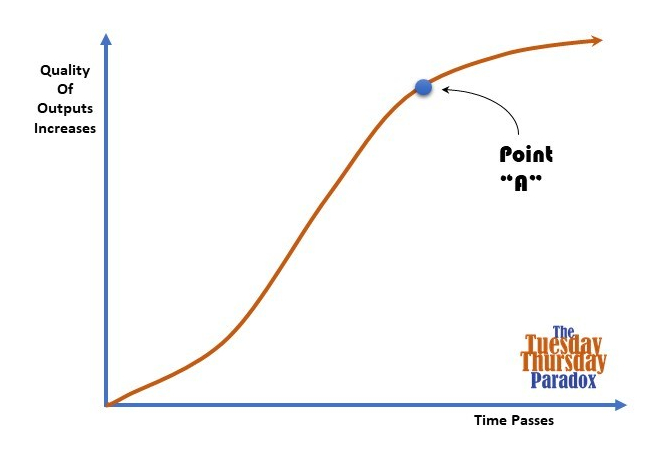

If we have limited time and lots of demands, the challenge is picking when to stop one task and move on, to know when something is “good enough”. The S-shaped Time-Quality curve shown here is perhaps slightly too simple to perfectly describe every task we do – but the basic concept probably holds pretty well. The main message from this curve is that we get non-linear value for our minutes. That is, some minutes give us more return than average and some give us less return – and so when we have time pressure, we need to try to optimise where we spend them.

In essence, the curve suggests that the first phase on a task is where the time we invest doesn’t really get us very far in terms of quality outcomes – because at that stage we haven’t done enough of the task to actually create an outcome at all. We might be doing useful or even necessary groundwork for a quality outcome, but clearly more time is required before we can consider it ‘done’.

Then there is a second phase where you get increasingly high returns for the time you put in. At some stage towards the end of this phase and maybe even right on the inflexion point, you reach Point A – the minimum feasible point at which the task could be realistically be considered “done”. Once this point is reached, we have to then make a choice about how much – if at all – we want to continue, because now we are using discretionary time rather than necessary time. Every non-linear minute spent here now needs to be a worthwhile investment, because it is time that could be used on other things.

As the curve continues beyond Point A, we see it flattens out into a phase of diminishing returns where every minute spent does less and less to further improve the quality of the final outcome. This is where we have to apply our judgement about just how good is good enough? The question is more complex even than that, because any analysis of how good it is needs to take into account the context and the opportunity cost. That is, does it need to be better in this specific circumstance? And what else isn’t getting done because I’m doing this task better?

Knowing when to stop and move on to another task (or just stopping!) is really important for our overall ability to manage time. Once we get beyond Point A and deep into Phase 3, where the improvement in quality from every minute spent on the task is getting less and less, there has to be a really good reason to keep going.

There are certainly entirely valid reasons to push on well-beyond Point A, that’s where the really great work gets done. However, I think knowing when to stop and not seek ‘perfection’ on everything is one of the real keys to bigger things like “time management” and “work-life balance”, amongst others.

A key idea to take out from the concept of the Time-Quality curve is not just that if a job’s worth doing, it’s worth doing well. That’s been beaten into us forever. What might be a more useful insight now is the unspoken corollary: that is if a job isn’t worth doing, it probably isn’t worth doing well. Or at least, if it’s done sufficiently well, there is no need to invest more time on it.

Anyway, enough on this subject. I think I’ve made my point sufficiently well for now, and I need to move on to some other important things.